When I first became passionate about cycling, the best frames--usually made from Reynolds 531 or Columbus SL tubing--featured intricately-cut lugs, like the ones made by Nervex:

|

| Nervex lugs with extra-long tangs on a 1950 Mercian Vincitore |

A good production frame like the Peugeot PX-10 would use Nervex lugs "as is"; custom frame builders might file them to even finer points, or make a cutout "window".

A few builders even cut plain lugs into their own distinctive patterns. The British builders in particular were noted for their distinctive scrolls, trellises and other shapes and patterns.

During the mid to late 1970s, however, bicycle makers--even the small-production custom builders--shifted to plainer "spearpoint" lugs. Sometimes those artisans filed them to elongate the "spear" or, as they did with Nervex lugs, cut a "window" in a particular shape, such as a heart, diamond or cloverleaf, into the body of the lug.

For all of the fancy lugwork, though, dropouts looked more or less the same. Again, some custom or low-production builders filed them or did other finishing work to make their bikes all the more distinctive. Still, because most high-quality dropouts looked so similar, there wasn't as much a builder could do to make that part of the bike stand out.

One notable exception this:

|

| Is it a honeycomb? Or a spiderweb? Did Huret make it? |

In 1974 and 1975, Gitane "Interclub" and "Tour de France" were made with this dropout. A few other bikes--all of them French--also featured this unique frame fitting.

Often called the "honeycomb" or "spiderweb" dropout, its provenance is somewhat mysterious. It's usually referred to as a "Huret" dropout because the bikes that came with it always seemed to have Huret derailleurs attached to them. (Yes, even on Gitanes, which were notorious for coming with parts that were very different from the ones listed on catalogue spec tables!) I could not, however, find this dropout in any Huret catalogue or brochure from 1974 or 1975--or, in fact, from 1969 through 1981.

From what I've gathered, it seems to be of good quality. One discussion board says that it was cast, rather than forged as Huret's (as well as Campagnolo's) road dropouts were. However it was made, the "honeycomb" or "spiderweb" seems to be robust, as no one seems to know of any that broke or otherwise failed.

Apart from its appearance, the "'comb" or "'web" had one other interesting--and useful--feature: without modification, it could accept Campagnolo, SunTour, Shimano and Simplex as well as Huret derailleurs. This is particularly serendipitious for anyone who wants to outfit an Interclub or Tour de France frame with modern components.

|

| Huret dropout |

Nearly all dropouts made since the 1980s are patterned after Campagnolo, which has a 10mm threaded mounting hole and a "stop" on the underside, at the 7 o'clock position. (SunTour and Shimano dropouts from the 1970s and 1980s were also made this way.) A Huret dropout also has a 10mm threaded hole, but its "stop" is at the four o'clock position.

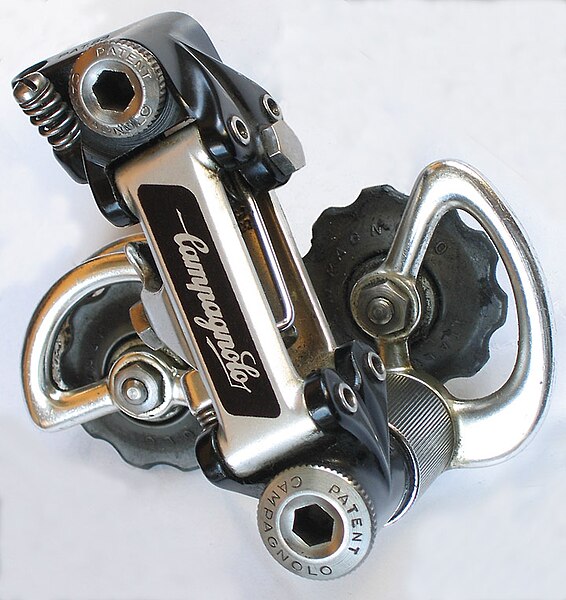

|

| Campagnolo dropout. Note the 'stop' at the 7 o'clock position, as opposed to the 4 o'clock position on the Huret. |

What all of that means is that a Campagnolo derailleur will fit into a Huret dropout, but it might mount at a strange angle, which could impede its shifting. A SunTour derailleur doesn't share this problem, as its angle-adjusting screw has a lot of range. In fact, Schwinn Superiors from 1976 through 1979 came with SunTour derailleurs mounted on Huret dropouts. So did some Motobecanes from that period.

On the other hand, some Huret derailleurs won't work on Campy dropouts at all. Two different versions of the Jubilee were made: one for Huret's own dropouts, the other for Campagnolo. Other Huret models, like early versions of the Success and Duopar, would work with adapters Huret offered; later versions of those derailleurs were made only to fit Campagnolo-style dropouts, which had become the de facto standard.

|

| Simplex dropout |

Simplex dropouts, as opposed to the others, had a 9 millimeter unthreaded hole and no "stop". If you want to use any other derailleur, you have to tap out the hole and grind a "stop": a rather delicate procedure, especially if the dropout was chromed, as it was on many bikes. Because SImplex derailleurs attached to the dropout with a recessed allen bolt that threaded into the derailleur's top pivot (in contrast to other derailleurs with top pivot bolts that threaded directly into the dropout), it could be used in a Campy dropout--with a "Class B" fit.

So...If you have a bike with the "honeycomb" or "spiderweb" dropouts, you have no reason to fear, at least according to everything I've read. But, honestly, you know you like it for its looks, or at least its uniqueness. They don't make them like that anymore!