Sometimes it seems that--here in NYC, anyway--there are two kinds of cyclists: the ones everyone hates and the ones other cyclists hate.

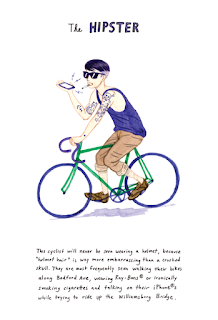

In the first category are, of course, hipsters with fixies and delivery cyclists riding against the traffic on city streets--and, worse, in bike lanes. The second group consists of tourists on rented bikes and hedge-fund managers on bikes that cost more than their secretaries make in a year, with lycra outfits to match.

Back in the '80's, the cyclists everybody loved to hate were the messengers. (I know: I was one.) And the ones who ticked off other cyclists were the Chinese (and, later, Mexican) delivery guys, who invariably were riding the wrong way just when you were flying down the street and couldn't steer out of their path.

And there was another category, of which I was a part: The ones fishermen hated. Now you might be wondering why a fisherman would hate a cyclist. Well, it has nothing to do with, "A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle." Instead, it had to do with the fact that very often, as we rode across the narrow pedestrian lanes like the ones on the Marine Park-Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge, men (almost always men) were casting their lines off, or had propped their fishing rods on, it. Sometimes they came close to snagging us, or we got a little too close to them (as if there were any choice!) and they claimed we were scaring fish away.

Perhaps the hate stemmed from resentment: Most of the anglers were poor or working-class, many of whom were immigrants. They saw us, on our expensive bikes, much as those who participated in Occupy Wall Street see bankers and the like.

Anyway, there are categories of cyclist--and haters--that didn't exist back then. Illustrator Kurt McRobert has catalogued them on his site.

(All images are from Kurt McRobert's site.)

In the first category are, of course, hipsters with fixies and delivery cyclists riding against the traffic on city streets--and, worse, in bike lanes. The second group consists of tourists on rented bikes and hedge-fund managers on bikes that cost more than their secretaries make in a year, with lycra outfits to match.

Back in the '80's, the cyclists everybody loved to hate were the messengers. (I know: I was one.) And the ones who ticked off other cyclists were the Chinese (and, later, Mexican) delivery guys, who invariably were riding the wrong way just when you were flying down the street and couldn't steer out of their path.

And there was another category, of which I was a part: The ones fishermen hated. Now you might be wondering why a fisherman would hate a cyclist. Well, it has nothing to do with, "A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle." Instead, it had to do with the fact that very often, as we rode across the narrow pedestrian lanes like the ones on the Marine Park-Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge, men (almost always men) were casting their lines off, or had propped their fishing rods on, it. Sometimes they came close to snagging us, or we got a little too close to them (as if there were any choice!) and they claimed we were scaring fish away.

Perhaps the hate stemmed from resentment: Most of the anglers were poor or working-class, many of whom were immigrants. They saw us, on our expensive bikes, much as those who participated in Occupy Wall Street see bankers and the like.

Anyway, there are categories of cyclist--and haters--that didn't exist back then. Illustrator Kurt McRobert has catalogued them on his site.

(All images are from Kurt McRobert's site.)